Primordial Architecture

Part I: Buildings vs. Architecture

Do people need architecture?

An architect nowadays is someone paid to fill a particular role in the process of creating a building.

But what is the role?

What value do architects add?

What is the value of a building?

What is a building?

We all have a sense of the value of shelter. Or most of us do. If you’ve ever experienced cold, heat, damp, noise, property loss, ergonomic discomfort or sunburn you’ve experienced the lack of shelter. If you’ve experienced the summer air in New York City filled with vapors of rotting trash, blaring fire engine horns, overcrowding, lack of seating, the constant bombardment of advertising and other forms of exposure and manipulation, you’ve experienced a lack of shelter. If you’ve experienced a farm with its unflinching work ethic, absence of shade, sweat, line dancing, slow wifi and people explaining the yin and yang of plant species, you’ve experienced lack of shelter. If you’ve slept in the woods at the mercy of wolves, bears, rats, snakes, irritant plants, lions, ants or sharks, you’ve experienced lack of shelter.

There are obvious ways to calculate a use value for shelter. We could deny it and resign ourselves to the will of apex predators. Or fight off the wilderness with clubs and sharpened spears. But weapons are also a form of shelter.

So we are all familiar with shelter. But is the presence of architecture the same as the presence of shelter?

A building is a technology, like a club or spear, crafted to keep natural irritants away. We have had buildings in some form or another for a hundred thousand years or so, since we began communicating our tool wielding knowledge and progressing from the vagrancy of cave or canopy living. A percentage of us have continued that vagrancy as a preferred and valid way of life. But the preference to build shelter has been democratically determined as the law of our civilization.

And what about architecture?

We have recognized the specialty for a few thousand years in various forms. In different degrees, the following definitions have typically been attributed to “architecture.”

1. The authority for durability, or the liability for human death, injury, disease or property loss caused by an unstable or unsuitable building.

2. The authority for economy, or the presence of good planning and procedure in construction, or the liability for expenditure.

3. The authority for beauty, or the presence of good taste in a building’s appearance, symbolic meaning or style of decoration.

These are approximate legal definitions that have historically regulated the exchange of architecture as a service.

In our current economy, one of three holds.

The first definition is generally delegated to related disciplines of engineering. A structural engineer takes on liability for death, injury or loss caused by collapse. A mechanical engineer takes on liability for death, disease or loss caused by unclean indoor air, unsuitable indoor temperatures, inadequate fresh water sources, or slip and falls under poor light. Only the small gaps in these responsibilities are filled by “architecture.” And only the hiring and coordination of these related disciplines is a product of “architecture.”

The second definition is often a responsibility delegated to a property manager, construction manager, project manager, or real estate lawyer. “Architecture” does not determine how much enclosed space a building user needs, the available resources to construct it with, its adherence to or variance from municipal planning codes, or the means and methods for constructing it. “Architecture” is again only responsible for “coordinating,” rather than determining, those economic aspects of a building.

And so we are left with the third definition of “architecture,” that elusive substance which determines good taste in a building’s appearance. And the responsibility for that lands on young, impressionable interns graduating from architecture schools, the creative class, characteristically underpaid and eager for experience and exposure, the determinants of success for a creative field in our current economy.

And in this state of being, relieved of the first two responsibilities and remaining with that of the creative taste-maker, influencer or aesthetic philosopher, the architect often becomes an entertainer. And buildings become a form of entertainment. And correct taste is governed either by familiarity or exoticism. There are those two criteria, or an eclectic combination of both, for marketing creative architecture as a service.

But back to the root of the topic, is it a building or is it architecture? The distinction becomes more relevant when architecture is no longer a technological profession. What is the mysterious architecture that is so necessary to consider, and pay a professional salary for, when a stable and functional building can be so readily constructed without it?

For this we could search philosophy for working definitions of beauty, meaning and good taste.

We could be platonic and say that beauty in a building is a representation of that building’s virtue. Perhaps the structural stability and interior comfort of a building could be expressed on its surface, using indicators of adroitness or warmth.

We could be Aristotelian and say that beauty in a building is dependent on good measure. Perhaps the correct number of columns were used to create the correct number of bays needed for entry and habitation. Perhaps the room proportions are ordered in such a way that they don’t create an obnoxious deviation from a familiar shape. Or perhaps these are also functioning representations of virtue that add stability or reduce echo, or make repetitious parts and pieces cheaper to manufacture.

We could be Kantian and abandon the idea that good taste is a mere reflection of functional virtue, and instead evidences a non-rational faculty that is more deeply embedded in us, one that we are too inadequate to quantify.

But buildings are much older than philosophy. And architecture, by association, is older than philosophy.

Kant makes a good point though about our being inadequate to quantify aesthetics.

Perhaps architecture is something buried deeper within our nature. It exists in our vagrant nature as a cave and canopy dwelling species, seeking comfort and security by recognizing it in our environment. Architecture then is an inevitable result of our tasteful actions. Something inescapable as discerning humans.

But it is not something necessarily human.

If we recognized architecture as apes, then less dominant animals can be assumed to recognize architecture as well. But is architecture a privilege of living things only, or is architecture chemical as well?

Miller Urey Experiment, 1952

The Miller-Urey experiment of 1952 is also an architectural study. The experiment was designed to recreate the atmospheric chemical conditions that enabled the first living cells on earth to form. The glass containers and plumbing loop used for the experiment could be seen as a house, sold to two young parents, methane and ammonia, to raise a family of repeating chemical sequences. Those chemical sequences would eventually build a house of their own, a “lipid bilayer” house, as a shelter in which to raise future generations of repeating chemical sequences. And the great descendants of those chemical sequences would eventually be the young creative class. So architecture in that sense is present at a chemical level.

Illustration of a Liposome and his wife, Micelle, via Universite Catholique de Louvain

Architecture was also present prior to chemicals.

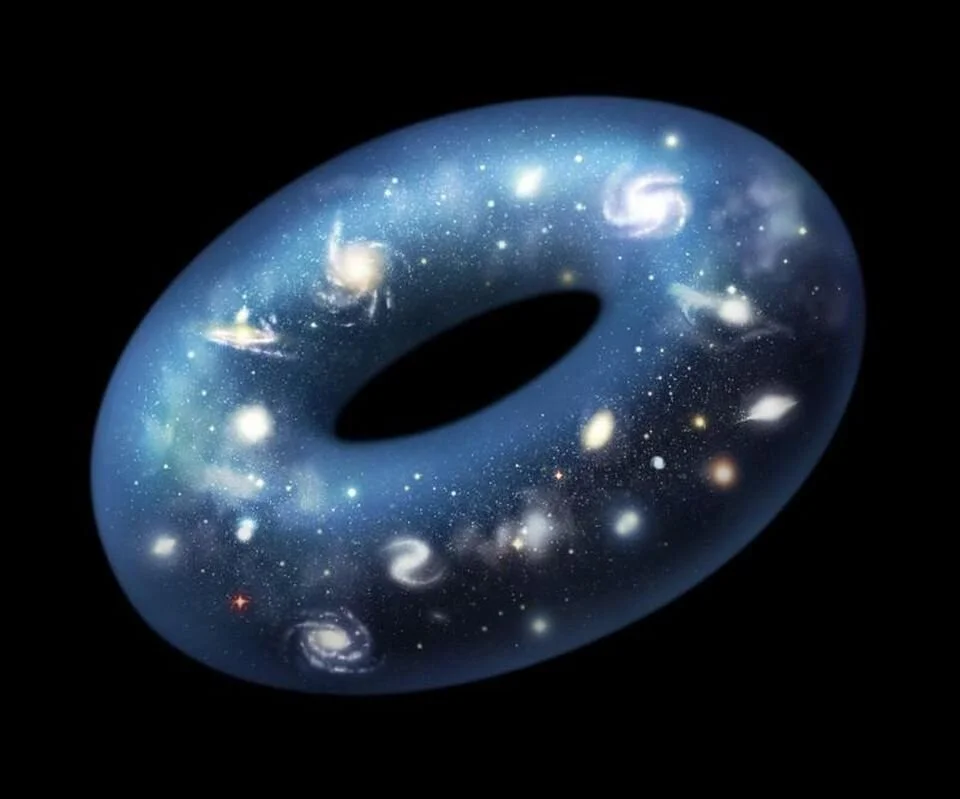

A theory of the genesis of matter suggests that the universe, in the moments before it exploded into the universe we know today, existed as an oscillating volume, smaller than a pinhead, whose contents fluctuated rapidly between matter and anti-matter. It seems there was a lot of indecision on the universe’s part, during this schematic phase, of whether a universe house would be better constructed from things or from non-things. And with a last minute decision from an agent operating in the interest of things, the universe was violently expanded into a collection of things.

Illustration of the universe as a donut, via Forbes

Architecture, in a more broad and confusing definition, is simply an ordering of things. But from the moment when time first existed, it has been applicable to events or decisions that have created the world in which we operate.

Chemical, biological and real estate agents act in ways which serve their interest or those of the parties they represent. And architecture is an ordering of conditions to serve those interests.

Lipids forming into a bilayer is an act of architecture. An ape selectively inhabiting one type of forest over another is an act of architecture. A Cro-Magnon identifying a rock-shelter is an act of architecture. A young creative professional annotating dry and wet panel joints for an aluminum cladding detail is an act of architecture. A project manager asking for 20 percent of the façade to be cedar ship lap is an act of architecture. And so on.

If we can consider architecture to be this ordering of things in the service of a particular interest, the aesthetic role of contemporary architect is essential. As a decorative advisor, the creative professional is responsible for determining the values of the client or public it serves. It does not receive uninformed instructions from a client. It imposes on the client more essential values.

The creative professional is a helpless carrier of eight billion years of decorative experience. It is unable to see forward from its eight billion years of experience. It should not rely on the need for exposure as an excuse to deny that eight billion years of experience. It is elected to its duties by a managerial body of its species to remember and perpetuate ordering factors inherent to the species interest. The responsible decorative decisions it makes are essential for the chemical and biological interests it represents.

And yes people need it.